Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Bacteria that harness water

Life thrives through energy. All creatures need energy to move, function, and grow. Yet, how energy is obtained by each organism varies. For example, some bacteria perform photosynthesis and obtain energy by fixing carbon through sunlight (phototrophs). In contrast, others get their energy by breaking organic compounds through enzymatic reactions (chemotrophs). A few decades ago, scientists discovered unique bacteria that harness energy by exchanging and uptaking extracellular electrons from the surrounding solid materials. These bacteria are known as Electroactive microorganisms (EAMs).

Various archaea, bacteria, and even some eukaryotes have been classified as EAMs and they harvest extracellular electrons produced from light and redox reactions between chemicals. For instance, processes like photocatalysis of metal sulfide, light exposure of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles, and geoelectrical electrons in deep-sea hydrothermal all generate extracellular electrons. Remarkably, water evaporation has been identified as a widely available source of extracellular electrons. The energy produced from water evaporation, known as hydrovoltaic energy, sustains microbial growth. A recently published paper by Guoping Ren and his colleagues has shed light on a bacterial biofilm that survived by harnessing the energy from water evaporation.

The system

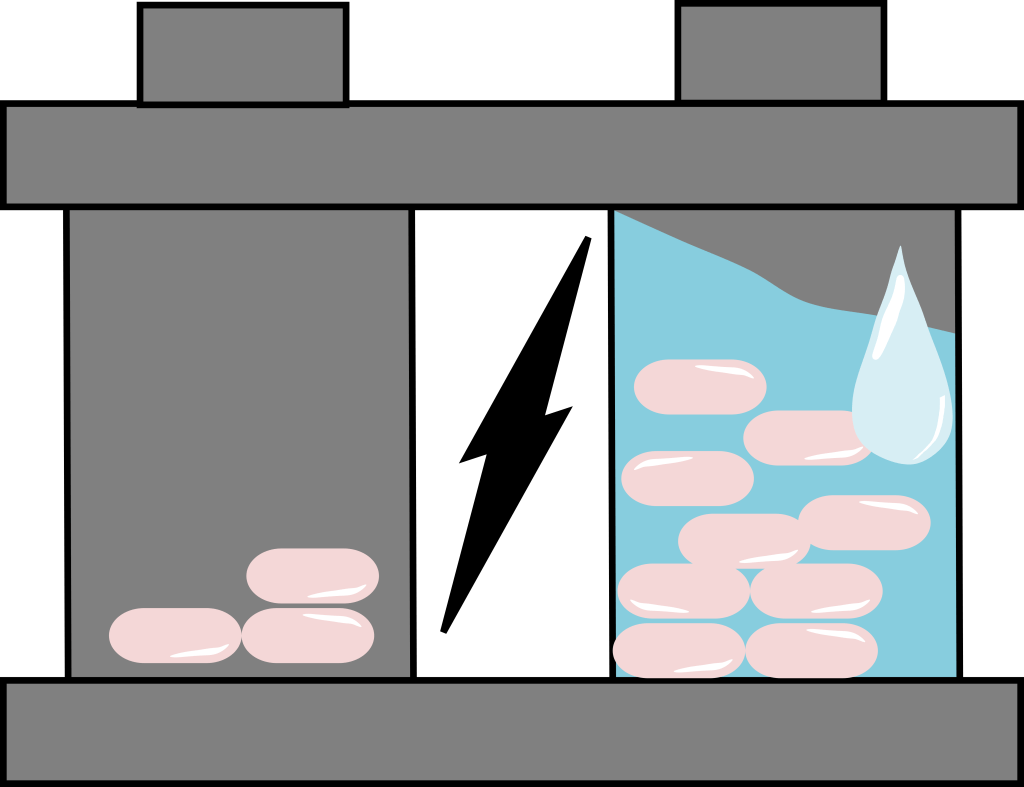

The system used in the experiment has a sandwich-like structure, where two electrodes were used to create external circuits. Positioned between them, the bacterial biofilm floats on a filter membrane. The water evaporation starts in the nanochannels between cells in the biofilm. Those channels are negatively charged. Therefore, they repel OH– and only allow H+ to flow. The external circuit will cause the electrons to migrate from the bottom to the top electrode where the electroactive bacterial isolates are located (Figure 1).

In this experiment, the bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris (an EAM bacterium) was used. It utilizes the collected electrons to fix CO2 into organic compounds and perform denitrification. The synthesized organic compounds are used in build-up biomass, while in denitrification the cell uses NO3– as a terminal acceptor in its anaerobic respiration reducing it into N2O/N2 (Figure 1).

In a fully sealed non-evaporating system, neither current nor cell growth was detected indicating that the produced hydrovoltaic energy is the sole source of bacterial growth. Moreover, a comparative analysis of the active genes in the biofilm with and without evaporation showed that genes involved in electron transport (e.g., nanowires, and flagella) were significantly elevated in the system.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the used system illustrating how evaporation generates hydrovoltaic energy and how the Rhodopseudomonas palustris harnessed the electrons. Image adapted from the original article https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49429-0.

How common is the phenomenon?

Water evaporation is a universal phenomenon that occurs in the ocean, river, soil, and on plant leaves. Therefore, the hydrovoltaic energy is believed to be abundant and widely available. However, two conditions must be present for the bacteria to utilize this energy. The first is the presence of the necessary machinery in the bacterial genome to uptake extracellular electrons. For instance, the co-authors tested four EAM species and two non-EAM ones. They found that non-EAM bacteria died out while EAMs survived, albeit in varying ratios. The second condition is the availability of the external electrical circuit which drives the electrons from the bottom to the top electrode making them available for the cells (Figure 1). This condition raises a question, can external electrical circuits be found in natural environments? The answer is yes! Many bacterial biofilms have microbial nanowires and conductive minerals indicating the potential for a self-contained electrical circuit within the biofilm. Taken together, the occurrence of both conditions suggests that this phenomenon might be very common in natural systems.

This study raises questions about how EAMs evolved and why. A few hypotheses have been proposed. One suggests that in a competitive environment, it might be beneficial to use a unique energy source to grow, like hydrovoltaic energy. The other hypothesis pointed to the early stages of the earth’s evolution when bacteria were the only evolved form of life and the atmosphere lacked oxygen. Hydrovoltaic energy may have served as a crucial energy source in such anaerobic conditions. Gaining such novel insight into how various bacteria thrive and respirate in nature expands our understanding not only about the ecology and evolution of life on earth but also paves the road for benefit from EM organisms in a wide range of applications including biotechnology, bioremediation, as well as biosensors.

Link to the original post: Guoping Ren, Jie Ye, Qichang Hu, Dong Zhang, Yong Yuan & Shungui Zhou. Growth of electroautotrophic microorganisms using hydrovoltaic energy through natural water evaporation. Nature communication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49429-0

Featured image: by author