Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Hijacking viruses to edit harmful bacteria

Our bodies are home to trillions of tiny organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, collectively known as the human microbiome. These microscopic inhabitants play a crucial role in our health, from aiding digestion to influencing our immune system. However, some bacteria can negatively impact our health, affecting the success of therapies, contributing to various diseases, and are even associated with cancer. This has led scientists to explore ways to alter the genes of these harmful bacteria.

Viruses to the rescue

Scientists have discovered a new way to change the genes of bacteria. They use viruses that usually infect bacteria – phages – and adapt them to carry and deliver gene-editing tools into the bacteria. These tools work like tiny scissors, cutting specific parts of the bacteria’s genes and changing how they work.

The adapted virus particles were designed to stick to certain markers on the bacteria. This lets them deliver the gene-editing tools to a large number of bacteria at once in the bacteria’s natural habitat. This way, they don’t have to replace all the bacteria with genetically modified ones, which could upset the balance of the microbiome. To prevent the spread of the edited genes, the scientists made sure that the gene-editing tool can only make copies of itself in the virus, not in the bacteria. This lets the gene-editing tool work well and make lasting changes in the bacteria.

Custom-made delivery

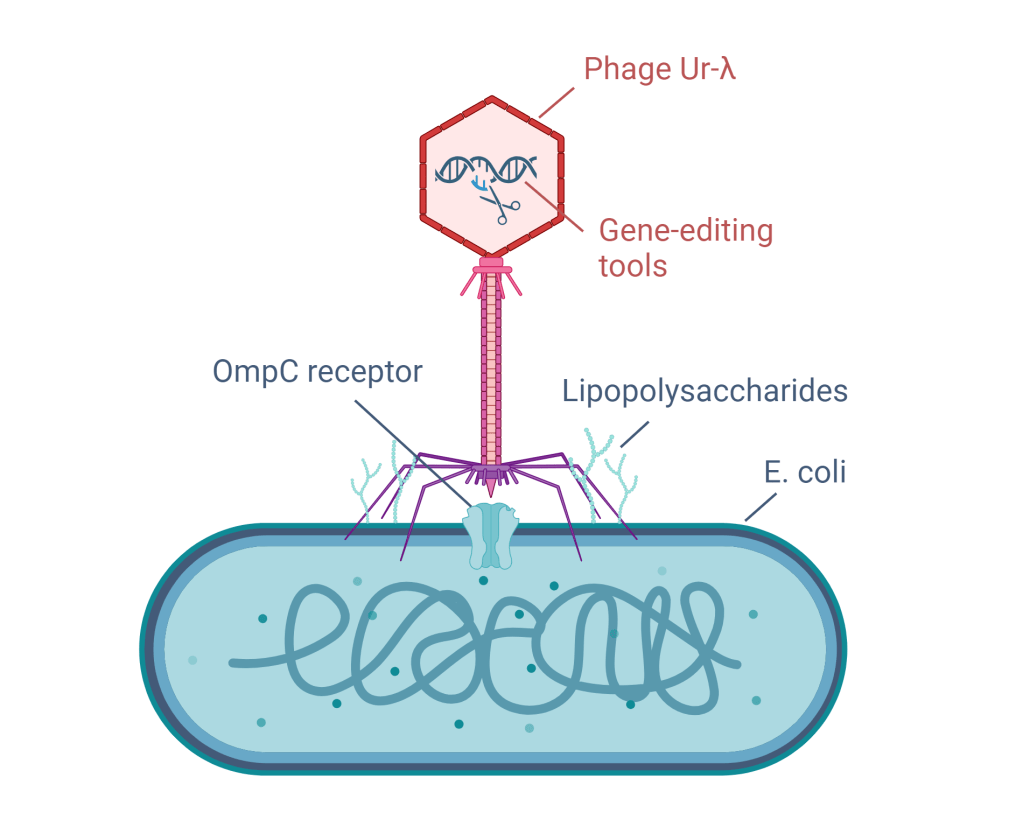

As a case study, the researchers engineered a virus called phage Ur-λ to better bind the E. coli bacteria, which can cause infections. The phage Ur-λ can stick to E. coli cells by the side tail fibre (like a rope) and a special protein gpJ at the tail tip (like a hook).

They made two changes to the virus:

1. The scientists made different types of hooks by joining other naturally occurring hooks to the original hook of the virus. And to make the virus even better at sticking to E. coli bacteria, they made sure that the new type of hook can stick to a special part of E. coli called the OmpC receptor, which allows entry of small molecules through the bacterial outer membrane.

2. To avoid the new hooks and the rope trying to stick to the same part of the E. coli cells, the scientists also made a new rope. They took a part of the original rope of the virus and joined it with the rope of a different virus. This new rope can recognize a different part of E. coli called lipopolysaccharides, molecules that help to maintain the structure and stability of the bacterial outer membrane and form a barrier to protect the bacteria from harmful substances such as antibiotics.

The custom-made phage Ur-λ, carrying gene-editing tools, sticks to an E. coli bacterium with its newly designed hook that recognizes the OmpC receptor and rope that recognizes the lipopolysaccharides. Image created by the author using Biorender.com.

To test the efficiency of these custom-made viruses in delivering their payload (the gene-editing tools) inside E. Coli, the researchers also added a gene coding for fluorescent protein inside. They then measured the fluorescence in different E. Coli strains. Their method worked well with many strains and showed improved efficiency with certain ones.

Success in lab and mice

The researchers tested the custom-made delivery viruses on three different types of harmful gut bacteria in the lab. They were able to deliver the gene-editing tool to over 90% of each type of bacteria. Then they targeted specific genes in the bacteria that are linked to disease. The results were impressive, with up to 92% success in editing these genes. This means they were able to effectively ‘cut out’ these harmful genes. Importantly, the method was very precise and didn’t cause unwanted changes elsewhere in the bacteria’s DNA.

Finally, the scientists tried their method in mice. The mice were given three different dosages of the costum-made virus. To check how well the base-editing tool worked, digital droplet PCR was used to measure the concentration of the edited gene in mouse stool samples. This technique divides the sample into thousands of droplets and then uses two fluorescent probes with a different color that bind either to the normal gene or the edited gene. By counting the fluorescent color of each droplet they can quantify the amount of the gene that was edited. Depending on the dose of the treatment, they were able to change 64-79% of the E. coli bacteria in the mice’s gut. The treatment didn’t seem to harm the bacteria or change the overall balance of the gut microbiome. When they selected one dose and gave the treatment for three days in a row, the success rate increased from 36% to 68%. Even three weeks after treatment, about 70% of the bacteria still had the edited gene.

This new method could be used to treat diseases by targeting the microbiome. It provides a new way to fight bacterial infections and study how specific bacterial genes contribute to disease. This research opens up new possibilities for treatments and helps us understand more about how bacterial genes affect our health.

Link to the original post: Brödel, A.K., Charpenay, L.H., Galtier, M. et al. In situ targeted base editing of bacteria in the mouse gut. Nature 632, 877–884 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07681-w

Featured image: created by author in DALL-E 3.