Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Summer Blues: A microbial link between hot weather and anxiety

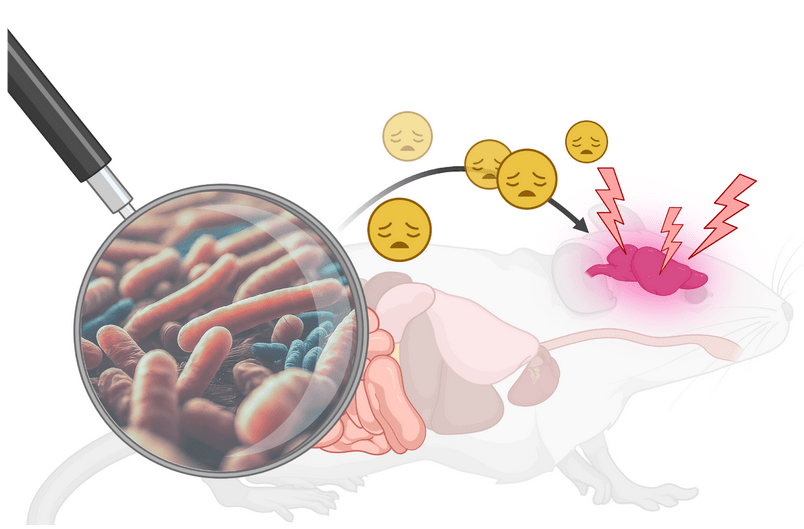

It’s summertime! The kids are out of school, the sun is out, and the weekends are reserved for finishing the perfect beach read by the water. But as global temperatures soar, summer may come with new challenges. A new study led by Huandi Weng at Jinan University suggests that long-term exposure to a hot and humid environment may promote anxiety-like disorders in mice by impairing the gut microbiota and driving inflammation in the brain.

Global warming is a public health threat

According to NASA, the global temperature has been steadily increasing, with the ten most recent years being the warmest ever recorded.1 Extreme heat carries deadly consequences, heat-related illnesses and exacerbations in conditions like stroke and heart attack have established extreme heat as the number one weather-related killer in the United States.2 Simultaneously, there is mounting concern over the increase in neuropsychiatric disorders, like anxiety and depression, which are now the sixth leading cause of disability in both high- and low-income countries. While previous studies have suggested that high temperatures are correlated with an increase in patients experiencing anxiety and depression, we still have a limited understanding of the biological mechanism behind this correlation which makes it difficult to identify good therapeutic options.

Now, Weng et al. have shown a surprising mechanist link between the changing climate and the increase in anxiety disorders that depends on metabolic and inflammatory signaling from the gut microbiome.

An anxious feeling in the gut

In this study, the authors subjected mice to a hot-humid environment (HHE mice) or normal conditions (NC mice) for 45 days and evaluated changes in their behavior and the gut microbiome. They found that the HHE mice consistently exhibited anxiety-like behaviors, spending most of their time hiding in closed portions of a maze. To support this, researchers used electrodes to record the synaptic currents in brain slices showing that the HHE mice had a significant increase in the frequency of excitatory synaptic currents.

Along with anxiety, the HHE mice showed significant decreases in overall body weight suggesting that the composition of the intestinal microbiome was different in the HHE mice.

Using a technique called 16s rRNA sequencing, which distinguishes bacteria present in a sample by sequencing a section of the genome that contains regions unique to each bacterial species, the authors found that Lactobacillus species were notably absent in the microbiome of the HHE mice compared to the NC mice. Without Lactobacillus species, the HHE mice also lacked metabolites produced by Lactobacilli that participate in chemical processes in the mouse body.

Because of the complexity of the microbiome, it can be difficult to show that changes to the microbiome are actually causing the observed effects. To show that the loss of Lactobacilli in the gut was a direct cause of anxiety, germ-free mice (which lack their own microbiome) were given a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) with feces from the HHE mice. After FMT, the germ-free mice developed the same microbiome as the HHE mice followed by anxiety-like behaviors. This suggested that the dysregulation in the gut alone was enough to promote anxiety in mice.

“Hello brain, it’s the gut microbiome calling”

But how do the changes in the gut signal to the brain to launch anxiety-like behaviors? The authors suggest that the key is an inflammatory response that travels through the bloodstream to the brain. When bacterial products enter the bloodstream, they interact with immune cells, stimulating the production of inflammatory signals. To get into the bloodstream from the gut and into the brain, bacterial products first cross through a barrier of cells. This barrier is normally held together very tightly by tight-junction proteins. However, using Western Blots to measure protein expression, the authors found that the HHE mice had decreased expression of tight junction proteins. The loss of tight junction proteins causes both the gut and the blood-brain barrier to become leaky making it easier for bacterial products to cross, ramping up the inflammatory response in the brain of the HHE mice and promoting the anxiety-like behaviors.

Probiotics as a therapeutic approach

Probiotic treatments are attractive therapeutics for diseases involving the microbiome because they’re non-invasive and easy to administer. In this study, Lactobacillus murinus was successfully used as a probiotic treatment. HHE mice fed L. murinus regained a normal gut microbiome and returned to normal behavior.

As global warming continues in an irreversible direction, this research has revealed a connection between hot temperatures and mental health disorders with the gut microbiome occupying a crucial junction. While this work was limited to mice, it’s an important first step to uncover the role of the gut microbiome in driving neuropsychiatric disorders and evaluating probiotics as effective therapeutics.

Featured image: Featured image created using AI generated images and BioRender.

Additional references

- Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-heat-related-deaths

- NASA. (2024, February 7). Global surface temperature. NASA. https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/?intent=121