Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbes on a diet: how to change bacteria’s appetite

Antibiotics. Insulin. Vitamin supplements. Biofuels. Detergents. What do these things have in common? They are all made by microbes. The biotechnology industry uses different microorganisms as tiny factories for large-scale production of widely used chemicals. The trade is relatively simple: they give us what we want in exchange for their favourite food and conditions that are just right for them to thrive in. But what if their favourite snacks are our favourites too? Could we teach them to like something else instead? An international group of researchers studied how a bacterium learns to eat what it is not used to, and how it adapts its metabolism to this new meal.

Microbes with a sweet tooth

Microbes used in the biotechnology industry particularly enjoy sugars (and who can blame them?). The universal favourite seems to be glucose, which we can easily get from starch (starch is basically a big molecule made of many glucose molecules linked together in a chain). In most cases, the starch comes from produce like corn, wheat or potatoes. But there is a catch – these are all things that we, humans, enjoy as well. What if there was a way to feed the microbes with something else, something that humans can’t eat anyway?

After a field of corn is harvested, a lot of green biomass, like stems and leaves, is left behind. There are lots of sugars in those as well, but they come in a form that we can’t digest. If you munch on a corn leaf, it will come out the other end having given no nutrients to your body (and potentially leaving you with an upset stomach). If this green waste, which we can’t eat anyway, could be used to feed the microbes (leaving the yummy produce for us), it would make the whole process cheaper and more sustainable.

Teaching a microbe to change its diet

But feeding industrial microbes with green waste instead of their favourite glucose isn’t so easy. It requires the microbe to ‘reprogram’ its metabolism to be able to eat other sugars, such as xylose, a component of the green waste and the second most abundant monosaccharide (simple sugar) on Earth after glucose. Many organisms used in biotechnology can’t feed on xylose, while others are able to use it, but very much prefer glucose. A team of scientists from Masaryk University in Prague, Czech Republic, in collaboration with researchers from Australia, Ireland, Germany and Spain studied how the bacterium Pseudomonas putida, one of the most used bacteria in biotechnology, adapts to feeding on xylose.

Pseudomonas putida grows fast and is relatively cheap to maintain, making it one of the go-to mini factories in the biotechnology industry. Because it is so commonly used, researchers study it from all possible angles to understand it as best as they can (check out an earlier post by maaikeloopt on how this microbe deals with being overworked). The researchers in this study wanted to see how a microbe learns to eat what it isn’t used to, and since P. putida can’t naturally feed on xylose, it made a perfect organism to address this question. Previously, another group of scientists engineered this bacterium to be able to take up xylose, but it did so very slowly, and the mechanism behind its new ability was still not clear. The researchers from this study wanted to understand exactly what happens inside the bacterium as it learns to change its diet. To answer their questions, they used a method called ‘adaptive laboratory evolution’ (ALE).

Evolution in a flask

First, the scientists engineered the bacterium by introducing extra pieces of DNA into it through horizontal gene transfer (HGT). During HGT, a bacterium takes up DNA that is floating freely around in the environment – in this case, the test tube. These DNA pieces contained genes that came from different kinds of bacteria that are naturally able to feed on xylose, and served as instructions for P. putida on how to do that as well. Then, the researchers gave this engineered bacterium xylose to feed on, and waited for it to figure out how to do that with the new instructions it was given.

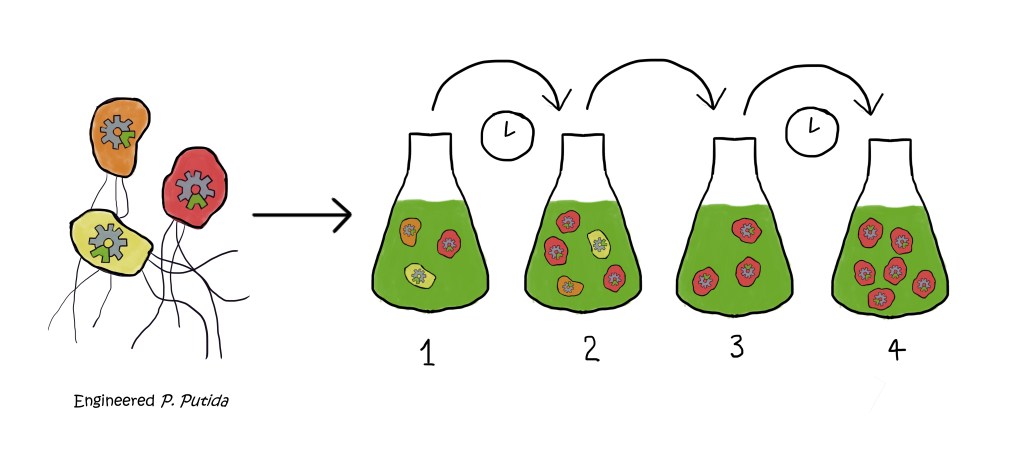

Simplified diagram of adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE). 1. The engineered bacteria are grown in a medium containing xylose. 2. Some grow better than others, meaning that they multiply more. 3. Part of the bacteria are transferred into a new flask. The ones that do well and multiply a lot have a higher chance of being transferred. 4. With time, the flask is full of the engineered bacterium that can grow on xylose. Image created by author using Krita 5.0.6.

But when a bacterium receives a new DNA piece, it can be quite confused at first and needs some time to rewire its metabolism. Some might have a more difficult time getting used to it than others, and here’s when ‘survival of the fittest’ comes in: some of the bacteria might randomly acquire new mutations that help it survive in the new environment, or that help it get used to the new DNA piece. With time, the bacteria that are better at adapting can further evolve and multiply, and become the perfect bacterium fitting the purpose – feeding on xylose.

The researchers then use other laboratory and computer methods to find out what happened inside this evolved bacterium when it was forced to switch its diet from glucose to xylose. This understanding will help scientists in the future to speed up the process of teaching other bacteria to switch their diets.

Link to the original post: Dvořák, P., Burýšková, B., Popelářová, B. et al. Synthetically-primed adaptation of Pseudomonas putida to a non-native substrate D-xylose. Nat Commun 15, 2666 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46812-9

Featured image: Illustrated by Michaela Krupová using Krita 5.0.6