Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Microbes & Metastases: exploring the bacterial residents of cancer

Bacteria are everywhere, including on and in our bodies. The collective of these microbes inhabiting the human body is called a microbiome, and it helps us digest food, plays a role in the development of our immune system, and can even protect us from other harmful microbes. Because bacteria are involved in so many processes in our bodies, it is no surprise that they can also find their way into tumours. But how exactly they get there and what they do remains a mystery. Could they potentially enhance the effects of cancer treatment? Or could they hinder it? Researchers from the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI) moved a step closer to answering these questions.

Metastasis is a secondary tumour

Most cancers originate with a ‘primary tumour’, but can also spread through the body to establish ‘secondary tumours’. These secondary tumours are called metastases, and they are formed by cancer cells travelling through the body, away from where the primary tumour developed. This way, cancer can spread into other organs and become much more difficult to treat. Scientists already know that primary tumours can house many different kinds of bacteria, and that these bacterial populations are different from those living in healthy parts of the body. To learn more about what effects tumour-inhabiting bacteria could have on cancer treatments, scientists from the NKI decided to investigate the bacterial residents of metastases.

Metagenomics – a DNA puzzle

To answer their question, the researchers took more than 4100 tissue samples (biopsies) from metastatic tumours, and used different methods to identify the bacteria found in them. One of these methods is metagenomics, which takes all the pieces of genetic information (DNA) found in a sample, compares them to a library of known microbes, and then tries to puzzle the pieces together to identify which microbes are in the sample.

Characteristics of bacteria in metastases

With the bacteria identified, they looked at what we already know about the species they found in the samples. They noticed that more than two-thirds of the bacteria living in tumours are anaerobic, meaning they thrive without oxygen – similar to, for example, the bacteria living in our gut. This makes sense, because the lack of oxygen (called hypoxia) is a common feature of most tumours, and a way by which they often manage to avoid the body’s immune response. The researchers also conclude that the make-up of a microbial community in a metastasis depends on the organ it forms in – and so a brain tumour would have different bacterial species inhabiting it than a tumour in the gut.

An enemy of our enemy is our friend

But what happens to these bacteria during cancer treatment? To answer this question, the researchers used tumour tissue samples from patients who were treated with different cancer therapies. They compared the samples from tumours before and after treatment, and noticed that in the tumours of patients treated with immunotherapy, the diversity of bacteria dropped considerably after the treatment. What’s more, they saw that this drop in diversity was even more noticeable in patients who got better after the treatment.

Immunotherapy is a treatment that boosts the patient’s immune system so that it is better able to find and fight cancer cells. The researchers think that this drop in bacterial diversity following immunotherapy could be caused by the ability of some bacteria to infect tumour cells. When a bacterium invades a cell, pieces of protein derived from it are presented on the surface of the infected cell like a flag. The cells of our immune system recognise this flag as a signal that the cell waving it has been infected and needs to be destroyed. The boost that the immune system gets from immunotherapy could make it better at noticing these flags and then killing the infected cancer cells.

A bacterium fighting on cancer’s side

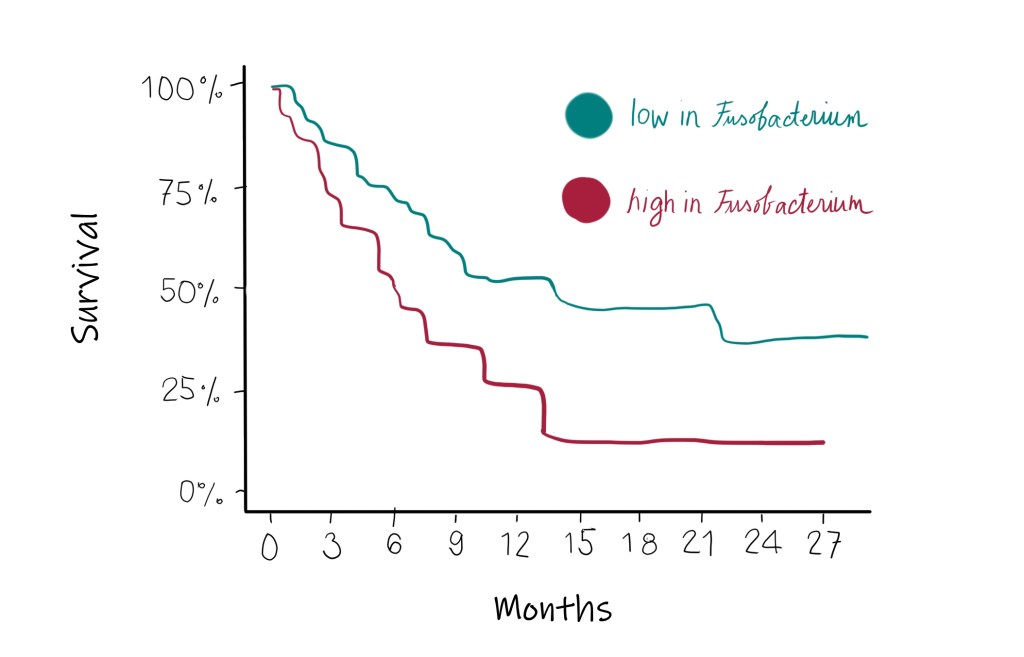

Unfortunately, some bacteria seem to be doing the opposite – making cancer treatment more difficult. They can help tumour cells avoid the body’s immune response, and so hinder immunotherapy treatments as well. In this study, researchers noticed that for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, the most common type of lung cancer) that had Fusobacterium in their metastatic tumours, the immunotherapy treatment was less effective. Other studies have found a connection between this bacterium and the growth of intestinal tumours, so it is possible that it can protect tumours in other cancer types too, including NSCLC.

With their results, the researchers show why it is important to study the bacteria living in tumours. These invisible cancer inhabitants seem to be able to influence cancer treatments, both positively and negatively, and could also become targets of new treatments in the future.

Link to the original post: Battaglia et al., A pan-cancer analysis of the microbiome in metastatic cancer, Cell (April 9, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.021

Featured image: Created by author