Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

The Sea Urchin Serial Killer

This post was written by Guest Author Emma Roman (@its_emmpirical)

Sprinkled throughout the hustle and bustle of tropical coral reefs are long-spined sea urchins. Unlike the soft blues, pinks, purples, and little orange bursts of their coral cityscape, these urchins, from the genus Diadema, are jet black. Their thin spines are mildly venomous, Tand they also love eating their greens. As they munch away at algae growing on the reef, Diadema allow more light and space for the local corals to photosynthesize and grow. Without them, reefs can become overgrown with algae, and the coral can die.

In the 1980s, a species of this urchin, Diadema antillarum, started dying quickly and seemingly without cause in the Caribbean. This happened again in the US Virgin Islands in early 2022, and researchers identified the ciliate, Philaster, as the primary suspect (1). Ciliates are single-celled eukaryotes and eat a variety of bacteria, algae, dead tissue, and organic matter. While these little guys may be the primary suspect in this story, in other situations, they can help keep coral reefs healthy by feasting on parasitic bacteria, dead corals, and by even being food for young coral polyps to eat (2).

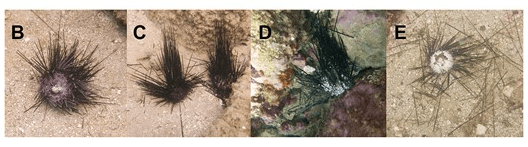

However, if these Philaster make their way into the long-spined sea urchin, they will feast on the urchin from the inside out. Infected urchins lose control of their long spines, either letting them droop or dropping them completely. The lack of spines leaves the animal defenseless to other predators, and as the infection progresses, their tissue dies and leaves their stark white skeleton visible. Infected urchins only have about a 15% chance or less of survival.

In July of 2022, a mass die-off of another species of long-spined sea urchins, Diadema setosum, happened in the Mediterranean Sea where the urchin is considered invasive. However, the parasite responsible wasn’t identified. The following year, D. setosum started exhibiting signs of infection in the Sea of Oman, its natural habitat. In a study led by Isabella T. Ritchie from the College of Marine Science at the University of Florida, the researchers wanted to know if the same parasite is killing both species of long-spined urchins and if it was spreading into D. setosum’s native range.

To accomplish this, researchers collected infected D. setosum, subjected it to DNA sequencing techniques, and confirmed that the same Philaster (from earlier reported mass deaths) infected the urchins from the most recent outbreak. To further confirm if Philaster was not specific to D. antillarum and could kill D. setosum, the researchers acquired healthy D. setosum and introduced some of the urchins to the parasite. One urchin was infected upon arrival. Five of the six urchins they put in an aquarium with the parasite died. Two urchins of the six they kept in aquariums without any Philaster also began to drop their spines but did not die.

Analyzing DNA samples from all urchins after the experiment, the researchers found increased amounts of Philaster in the bodies of the urchins who succumbed to infection, including the urchin that was already infected upon arrival. The urchins that were not did not get introduced to the parasite had extremely little Philaster in their tissues, except the two that began dropping spines which had low amounts of the parasite in their bodies.

This study suggests that a mass die-off event for D. setosum in its native range of the Indo-Pacific could be right around the corner. The researchers report that other genera of urchins – such as Echinothrix – have shown signs of the same infection. This means the Diadematidae, the family which Echinothrix and Diadema fall into, is in danger.

If we don’t study how this parasite moves and infects, the serial killings of urchins will continue. If we don’t continue to try, one of the reef’s top algae-eaters may disappear. Algae will coat the reef in a thick blanket, leaving the once vibrant metropolis desolate and drab. There is hope though, because we now know who to look for. We’ve identified a suspect and found them guilty. Now, we just need to wrangle Philaster back in. Once we have done that, Philaster can continue being an important member of coral reef security by eating parasites, rather than being one itself.

Link to the original post: Isabella T Ritchie, Brayan Vilanova-Cuevas, Ashley Altera, Kaileigh Cornfield, Ceri Evans, James S Evans, Maria Hopson-Fernandes, Christina A Kellogg, Elayne Looker, Oliver Taylor, Ian Hewson, Mya Breitbart, Transglobal spread of an ecologically relevant sea urchin parasite, The ISME Journal, Volume 18, Issue 1, January 2024, wrae024, https://doi.org/10.1093/ismejo/wrae024

Featured image: https://www.stockvault.net/photo/214441/utils/common

Additional sources (if applicable)

Reference 1: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adg3200

Reference 2: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10617535/