Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

The Dope Secret of Tryptophan

Our body is a complicated well-oiled machine whose inner workings we are still trying to understand. It’s almost as if we are trying to decode an encrypted book. Amino acids are the building blocks for proteins and enzymes within our cells, like how letters make up words, that then go one to form more complex sentences. Some our amino acids can’t be produced by the body, making it essential to consume them through our diet. One such amino acid is tryptophan, whose powers remained elusive until now.

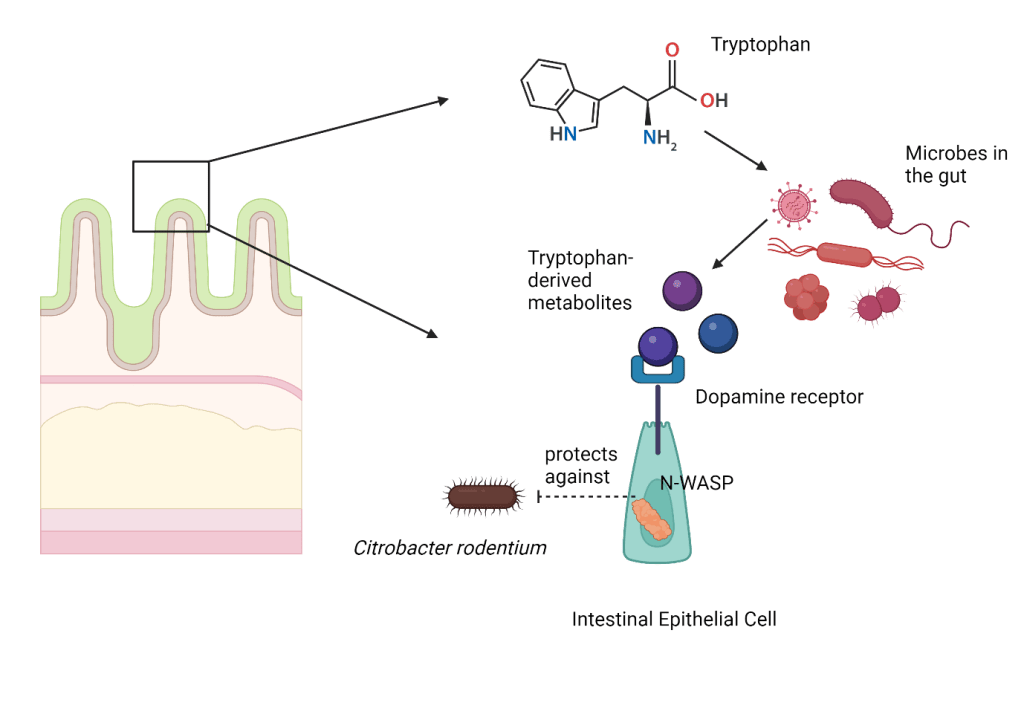

In effort to understand why tryptophan was essential and what are its unique powers, a recent study , using mice, found that a diet rich in tryptophan can protect the intestinal lining against certain bacterial infections. Citrobacter rodentium was used as a model pathogen in mice due to its similarity to E. coli infections in humans. The authors then wanted to understand how this protection is mediated. Interestingly, this protection only occurred when other microbes were present in the mice, suggesting that the tryptophan was utilized by these gut microbes to defend against the infectious bacteria.

Microbes need to sustain themselves and often rely on their host for nutrients which subsequently breakdown into smaller molecules to generate energy to function, just like we do. The resident gut microbes were found to be eating tryptophan and releasing tryptophan-derived metabolites in the gut. This metabolic phenomenon could provide protection to the intestinal lining when released by the microbes.

The authors used techniques like mass spectrometry to identify what this metabolite could be and found not one, but three such metabolites! These metabolites were present at higher concentrations in mice that were fed tryptophan rich diet, and thus are the main culprits for the observed protective effects seen.

The authors researched further to fascinatingly find that these three metabolites were able to activate dopamine receptors. Dopamine is a type of neurotransmitter that plays multiple roles in cells, like motor moment and cognition, but more commonly it serves in the reward-motivated behavior. There are a family of proteins that recognize dopamine termed as dopamine receptors and they are expressed in various cells in the body like neurons, renal cells, and intestinal cells. In people suffering from diseases like Parkinson, dopamine signaling is dysregulated. Interestingly though it is believed that more than half of the dopamine levels in the body are produced by the microbes living in the gut. The authors wanted to further understand this interaction.

Based on experiments performed using cell-lines, they decided to focus on a dopamine receptor called DRD2, which was the most prominently affected by the tryptophan-derived metabolites. They blocked the dopamine receptor DRD2 using an inhibitor (a molecule that would bind to the protein of interest and prevent it from carrying out its normal function) and saw that those mice were no longer protection against infection whereas when the dopamine receptor was activated, using an agonist (drug that binds to receptor and activates it), the protection against the infection was seen.

This receptor, specifically when expressed by intestinal epithelial cells, offered this protection. Epithelial cells are cells that come from the surface of the body and their primary purpose is to protect against invaders, acting as a barrier. The authors showed that the activation of the dopamine receptor in epithelial cells results in a chain of signaling pathways within the cell that lead to the degradation of an important protein called N-WASP (Neural Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein). Bacteria need to interact with our cells to be able to invade them and attack them. They use one of the motor proteins (actin) in the cell to do this. This protein production is regulated by N-WASP. So, when N-WASP is degraded, the availability of the motor protein, actin, to the bacteria is restricted, leaving the bacteria with no choice but to exit the system unable to attach and attack our intestinal cells.

This study is particularly interesting since it highlights how a neurotransmitter receptor is used in an unusual way to protect against pathogens in the gut. The pathogen was unable to find a home in the body because of tryptophan derived metabolites released by other microbes already present in the gut. These metabolites activated the dopamine receptor and stopped the binding of the infectious bacteria from attaching to the intestinal lining. These other microbes don’t want unwanted guests in their home, forcing them to share resources thus minimizing food and space available for themselves. This is an example of colonization resistance. There are also exciting implications to public health initiatives like eating food rich in tryptophan to harness this protective function, encouraging further studies on how else increased tryptophan influence the health of humans, inspiring future therapies.

Link to the original post: Scott, S.A., Fu, J. & Chang, P.V. Dopamine receptor D2 confers colonization resistance via microbial metabolites. Nature 628, 180–185 (2024).

Featured image: Source: Zeiss; “Human epithelial cell infected with Chlamydia trachomatis”