Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Are carrots the key to frog conservation?

We can’t see them, we can’t feel them, but billions of microorganisms live on our skin! This microbial community (the skin microbiota) is composed mainly of bacteria but also of fungi and mites stuck together at the surface of our skin. It forms a veritable shield preventing microorganisms that could harm us (pathogens) from entering our body!

It is the same in other animals, for example in amphibians. They have very thin skin used for breathing with some species breathing only through their skin! It is very fragile! The mucus covering it prevents it from drying. Their skin microbiota also plays a major role in their skin health especially for pathogen defense as it forms a protective barrier, produces antimicrobial and antifungal molecules, and stimulates immunity.

One of the major threats for amphibians in the wild is a pathogenic aquatic fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) which causes chytridiomycosis, an infection blocking respiratory organs. A recent studie has shown that diet can influence responses to infections through the gut microbiota but little is known about the influence on the skin microbiota.

In this recent study, researchers wanted to understand whether carotenoids (nutrients involved in immunity and coloration) could influence skin microbial communities’ composition across different life stages in the southern corroboree frog, a critically endangered frog species endemic from southern Australian and threaten by B. dendrobatidis.

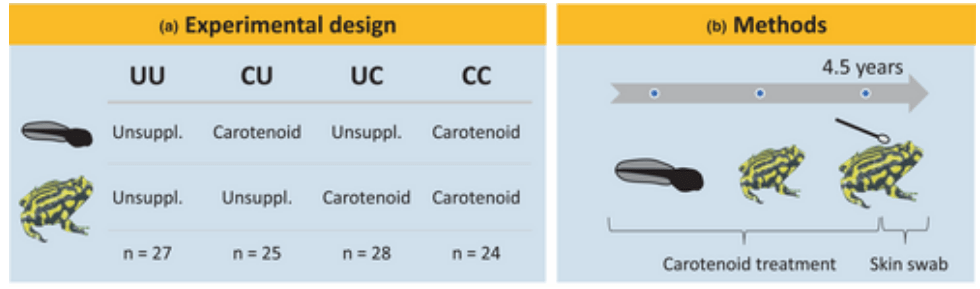

104 captive frogs were kept and raised in the lab under conditions that mimic natural conditions. They were divided in 4 groups depending on how they were fed (figure a):

- UU group: these frogs were not supplementary fed with carotenoids during their entire life. They represented the control group.

- CU group: these individuals were given carotenoids only when they were tadpoles

(before their metamorphosis from tadpoles to adults) by mixing their food with a

carotenoid mixture. - UC group: these individuals were given carotenoids only when they were adults (after

their metamorphosis) by giving them crickets previously fed with carrots and mixed

with a carotenoid mixture. - CC group: these frogs were supplementary fed with carotenoids during their whole life.

At 4.5 years old the skin of the frogs was swabbed to sample their skin microbes (figure b). Identification of the microbes relied on the identification of barcodes hidden in their DNA. Every species has a different barcode (like each item in the supermarket has a different one).

A DNA sequencer can read these barcodes, give you a sequence of letters and specific programs can then identify the microbial species (and even the different microbial strains) to which this sequence belongs by comparing it to a database containing all microbial barcoded associated with the name of the species they belong to. This is like scanning your articles at the cash desk of the supermarket, the cash desk reads the barcodes and the computer in which all item information is stored then identifies to which item it belongs and what its price is! Once the microbes are identified, microbial communities are usually described using diverse measures to compute the number of species present and their abundances.

The authors found that carotenoids influenced the skin microbiome composition of these frogs even 4.5 years after diet supplementation suggesting a role of diet in shaping the skin

microbiota in amphibians. Ingesting carotenoids after the metamorphosis increased the total diversity of the skin microbiome meaning there were more different microbial species after the frogs had carotenoids when they were adults than when they did not receive carotenoids. There was little effect when they received carotenoids before their metamorphosis.

Some bacterial genera were more abundant when frogs received carotenoids at any developmental stage: Enterococcus, Lactococcus, Enterobacter, and Kluyvera. Some of these bacteria such as Lactococcus garvae have previously been shown to provide protective effects against chytridiomycosis infections. This result suggests carotenoid supplementation could be an approach to increase the resilience of amphibians in conservation programs. Yet, further studies are required to truly understand the underlying mechanisms involved between skin bacteria and the host response against chytridiomycosis infections and how carotenoids modulate this interaction.

This study is one of the first to highlight the link between diet and the skin microbiota in amphibians and how it could influence the host’s response to pathogens. And, no, giving carrots to frogs in the wild won’t save them! But these promising results do open the way to thinking about conservation strategies, especially knowing the availability of nutrients in the wild depends on the resources present, which are often impacted by climatic conditions, with these frogs also being threatened by drought in their habitat.

Link to the original post: Risely, A., Byrne, P.G., Hoye, B.J., Silla, A.J., 2024. Dietary carotenoid supplementation has long-term and community-wide effects on the amphibian skin microbiome. Molecular Ecology 33, e17203.

Featured image: Scott Eipper (https://www.flickr.com/photos/scott_eipper/38711647624)