Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

Scouting for new antibacterial drugs targeting unexplored pathways

Written by

Eisha

Antibiotics have been popular since their discovery for their ability to kill bacteria, particularly those harmful to humans. What’s even more fascinating is that they are produced by other bacteria or fungi to curb their bacterial neighbours- a process accidently discovered by Alexander Fleming which gave the world an antidote to treat deadly bacterial infections. These antibiotics are grouped based on how they work. For instance, beta-lactams such as penicillin target the outer covering of bacterial cells, while chloramphenicol focuses on stopping their protein production. In this manner, the antibiotics we know act on specific bacterial cellular processes.

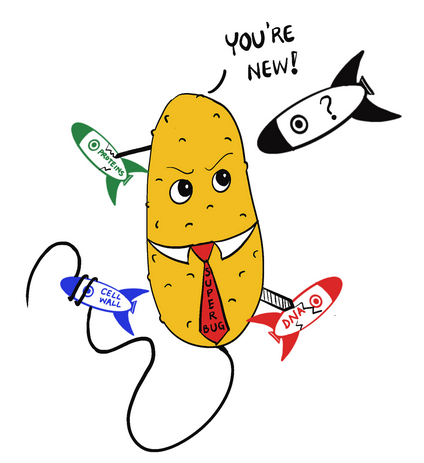

As much as we know about how antibiotics work, we have also realized their limitations. Bacteria can rapidly develop resistance to usual antibiotics making them useless against prominent infections. The increasing global resistance to antibiotics is a problem and superbugs- bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics- are rapidly emerging. This has prompted scientists to look for new antibiotics and test non-antibiotic drugs for their ability to kill bacteria.

In a recent study published in Science, Mariana Noto Guillen and colleagues investigated how a wide array of drugs affect the growth of E. coli, a common gut bacterium that can sometimes cause opportunistic infections. These drugs are commonly used to treat non-infectious diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and depression. In the pool of over a thousand drugs, they found 176 with potential antibacterial activity. Their next challenge was to examine the cellular process by which these drugs function and whether bacteria can evolve resistance to them.

For this, the authors used E.coli mutants with single gene deletions and added genetic barcodes to them. They mixed these mutants and grew them in two settings: with and without drugs. The drug concentration was set to inhibit at least 50% of growth. Then, they isolated the DNA and sequenced the barcodes to determine how often each gene mutant appeared in the presence of the drug. If the mutant was missing from the pool, it meant losing that gene made the bacteria more sensitive to the drug. If a mutant was more common, it meant losing that gene made the bacteria resistant to the drug.

Furthermore, the researchers utilized network-based analysis to find similarities among the studied drugs. By comparing the targeted genes to those processes known for antibiotics, authors noticed that nonantibiotics target a different set of pathways, with only common targets being transport systems involved in drug uptake by bacterial cells. This opens the possibility of uncovering unexploited targets for inhibiting bacterial growth.

However, the study also highlights potential challenges associated with drug resistance. The researchers observed that resistance to these drugs might involve mutations in genes encoding drug transport systems. While this drug-transport based resistance may confer resistance to specific drugs, it could also lead to broader resistance against chemically similar compounds or even cross-resistance to antibiotics.

This study sketches a complex interplay between drugs designed for non-infectious conditions and their effects on bacterial growth. By unravelling the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions, the researchers pave the way for the development of innovative approaches to combatting bacterial infections and tackling the growth threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Link to the original post: Mariana Noto Guillen et al., Antibacterial activity of nonantibiotics is orthogonal to standard antibiotics.Science384,93-100(2024).

Featured image: A cartoon representation of a superbug looking at a new antimicrobial while dodging the targeted antibiotics. Procreate art by Dr. Eisha Mhatre