Breaking down the microbiology world one bite at a time

When #2 can be your #1 solution…

Written by

Rachel Dumez

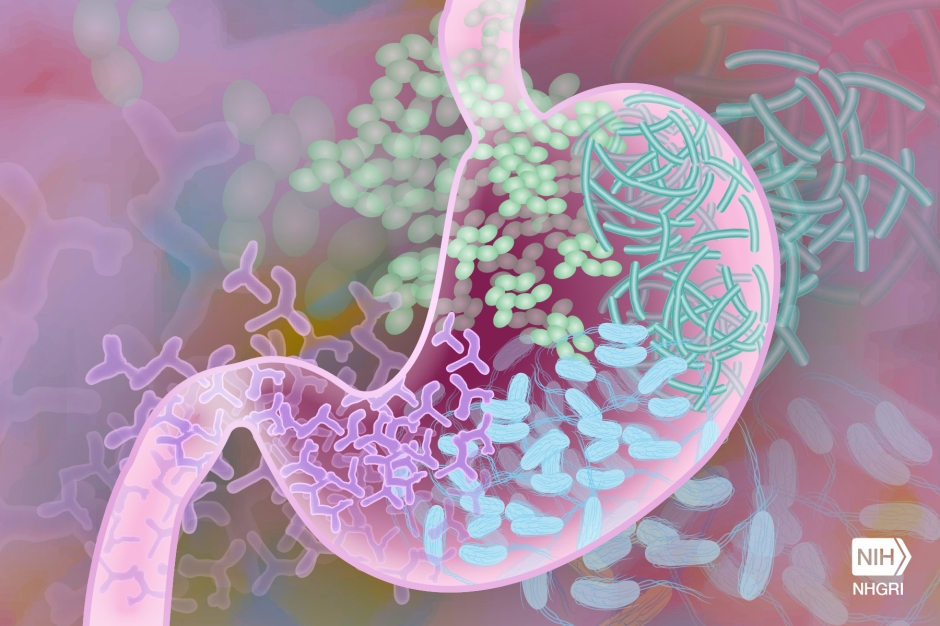

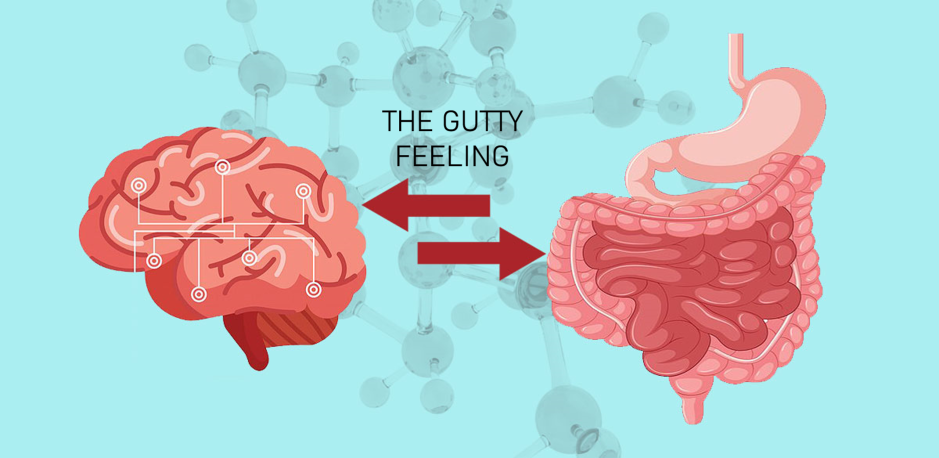

Imagine a diverse, thriving metropolis, such as New York City. A true melting pot with a vast community that thrives off the synergy of people from all backgrounds living and striving for the American Dream in a stable, yet delicate, balance. Well, your colon, also referred to as the large intestine, is the New York City of your gastro-intestinal (GI) track hosting an immense diversity of microorganisms. With more than 10 billion residents that represent over 1000 species and hail from all the branches of the tree of life (archaea, bacteria, and eukarya), the gut microbiome is a bustling metropolis in which a cacophony of microorganisms work together for the greater purpose of helping you thrive. This community, much like New York’s, relies on stable environmental conditions to persist and flourish. When a natural disaster occurs, like a category 5 hurricane, residents are forced to evacuate. Infrastructure is destroyed, and opportunistic pests can wreak havoc in the wreckage. This level of devastation can also happen in your colon, especially following an acute trauma or an assault on the current residents, such as having surgery and subsequently taking antibiotics.

One particularly nasty pathogen responsible for nearly half a million infections in the United States annually, is the bacteria Clostridium difficile (C. diff). C. diff is commonly acquired in hospitals and given the opportunity to take over your gut microbiome, it can cause symptoms ranging from those associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) to severe colitis and even death. Luckily physicians and scientists have developed effective therapies to reestablish the gut microbiome and eliminate the devastating impact of C-diff infection on your health. These treatments, while extremely effective at resolving the acute threats of C-diff, do not always eliminate the non-life-threatening but still debilitating IBS symptoms.

So, how do doctors help your body reestablish a health gut microbiome? And what needs to happen in your colon to eliminate the crampy stomach aches sometimes left behind after the eminent threat of C-diff infection has passed?

Let’s find out:

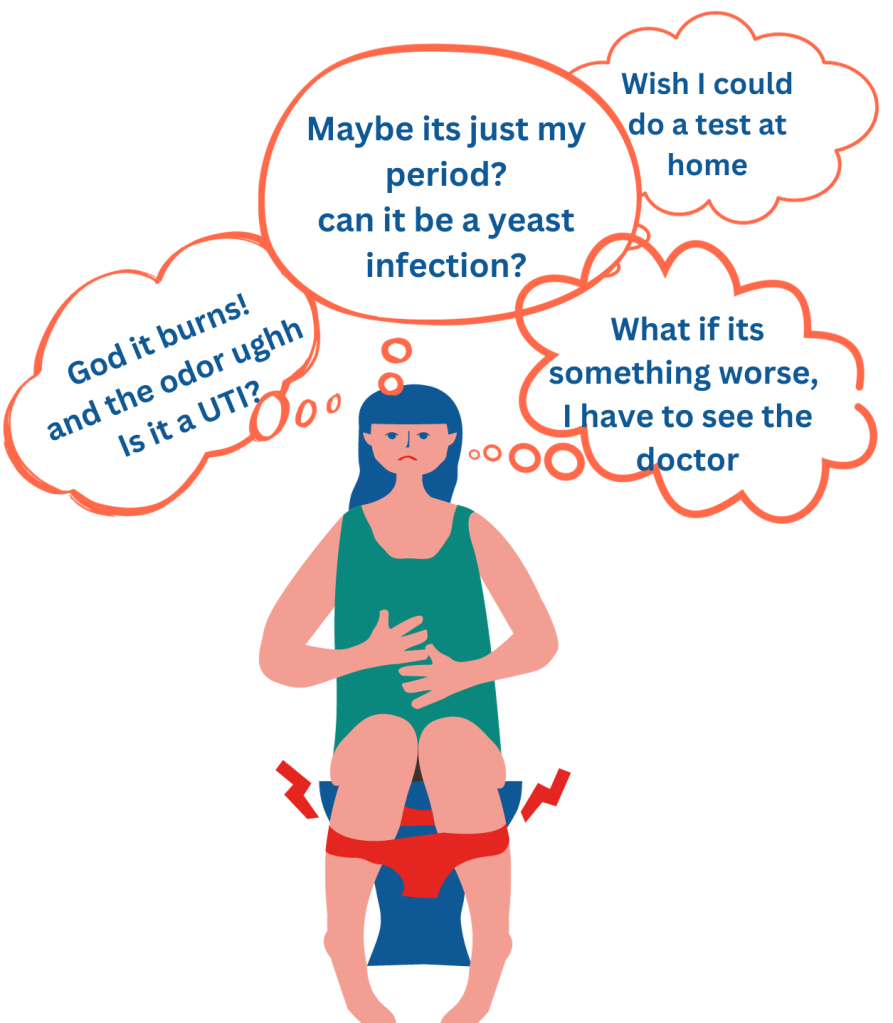

You enter the hospital, don your hospital gown, and remind yourself that this is a routine surgery with a high success rate. The procedure goes well, but unbeknownst to you the sly microorganism, C. diff, has entered your GI tract. It manages to travel through the hostile stomach environment and hitchhike all the way to your colon where it takes up residence within your gut microbiome community. It is a genial member of the neighborhood, for now. Your post-op is complete, and you are discharged with instructions to pick up antibiotics from your local drug store. You follow doctors’ orders and complete your entire prescribed dosage of the antibiotic. You are thankful that the whole ordeal is in the past. However, not even a month goes by before you are constantly plagued by stomach aches, cramps, and fits of diarrhea. Following a quick visit to your general practitioner, you are labeled as part of the ever-rising number of Americans that suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). But how did this happen?

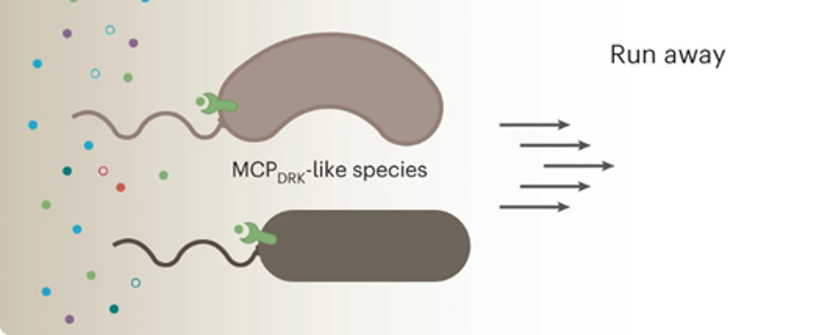

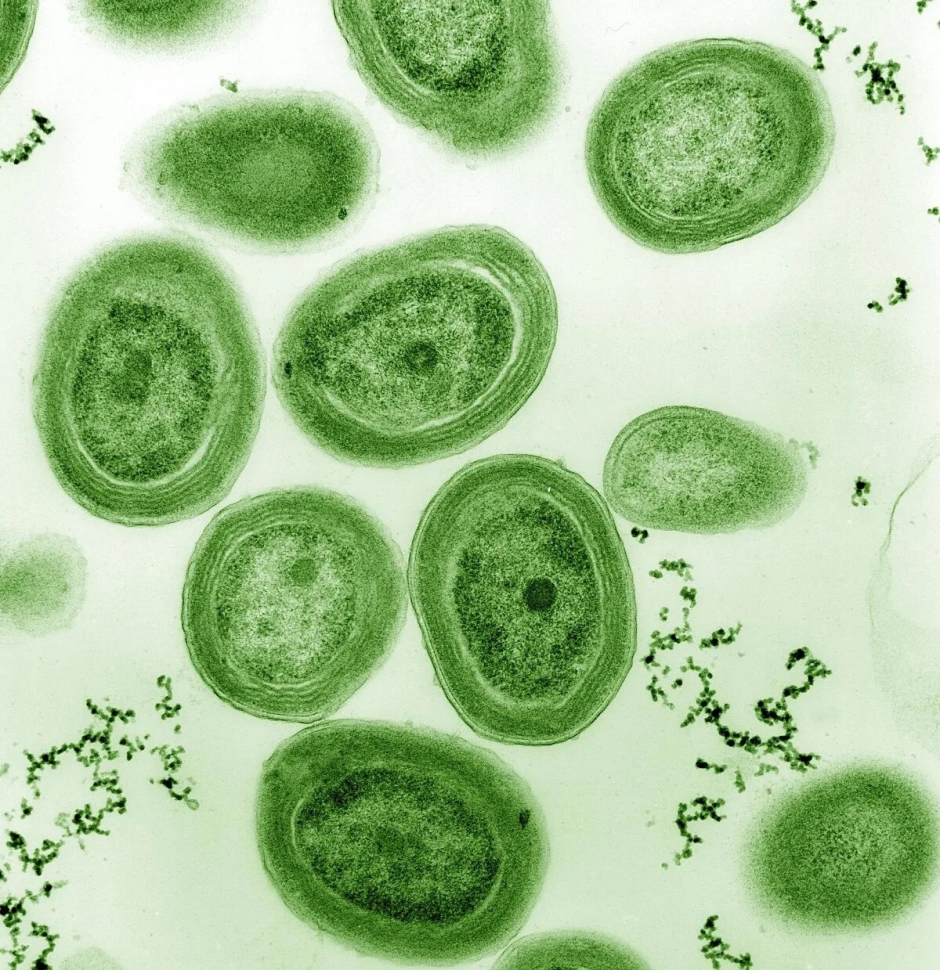

The antibiotic regiment you took as a precaution after your procedure is a hurricane in your colon. The residents, your native gut bacteria, were forced to evacuate, and their home, your colon, was severely damaged (Figure 1). Following the storm, like the rodents that infiltrate a city after a devastating natural disaster, C.diff has a chance to take a stronghold as the citizens collect their bearings. In the case of your colon, C. diff, sized its moment. This bottom feeder, or opportunistic pathogen, thrives in these tumultuous conditions and is responsible for you developing IBS following antibiotics. You have the required testing done and the lab results confirm what you already know, your diverse, vibrant, colonic metropolis is now dominated by one overzealous pest that is causing increased damage to your colon as it exploits its neighbors and monopolizes resources. So how can you avenge this dangerous coup and restore a balanced bowel?

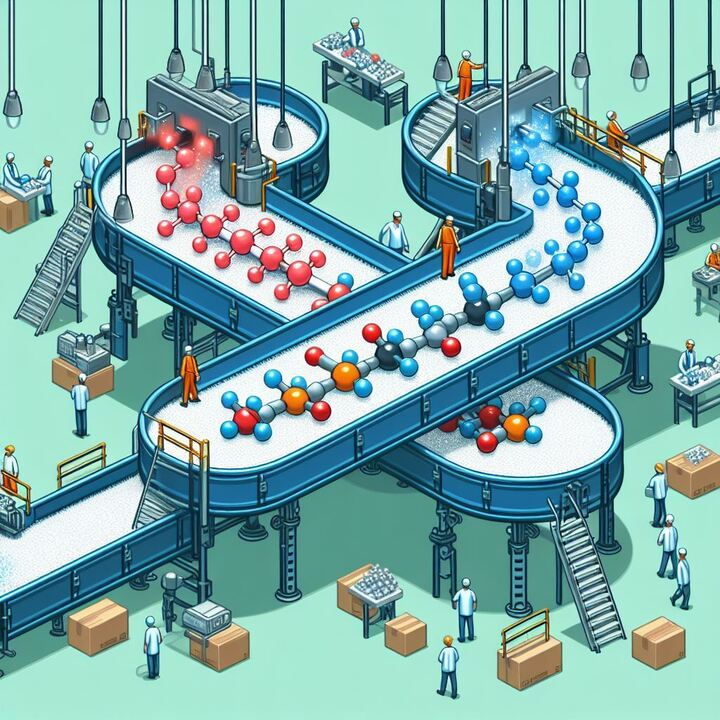

Well, this is where a good Samaritan comes in and shares their number two. Yes, their poop. Researchers have shown that fecal transplants can be extremely successful for the treatment of C-diff and the associated IBS symptoms 1. Doctors take stool samples donated by healthy people, concentrate the microorganisms, and then implant the solution through a colonoscopy-like procedure (Figure 2). So, you head back to the hospital, and receive a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). Inside your colon there is a massive influx of new residents that get to work cleaning up the damage and rebuilding a vibrant community that will again help you thrive. You experience almost immediate relief; you have not had IBS symptoms for weeks and C-diff microbes are nowhere to be found in your lab results. Now you can truly put the whole thing behind you and move on with your life. Thankfully your experience falls within the majority. Your body responded well, and your colonic environment went back to pre-surgery “normal”. But not everyone is that fortunate.

(Infographic adapted from Knowable Magazine article by Kendall Powell)

While FMT treatment has a high success rate, doctors and scientists are finding it difficult to create a standardized procedure that works for every patient. Therefore, it is important to gain a better understanding of what exactly happens inside the colon of patients, especially those that respond well, following FMT.

A recent study demonstrates that in addition to a restored biodiversity, levels of key indicators involved in protective type-2 inflammation are also restored to a healthy baseline following FMT2. In the process of rebuilding their home in your gut, your colonic environment was also restored to a healthy state and your IBS symptoms subsided. Unfortunately, that does not happen in everyone’s colon after FMT and doctors and scientists are still trying to understand why. One hypothesis is that even though the microbial metropolis is repopulated with a vast diversity of species and the pests have been evicted, the environment is not restored, and people can still suffer from IBS symptoms. To continue the storm analogy, even after the storm has passed, residents have returned, and the visible damage has been fixed, there can still be inconspicuous, health threatening, damage caused by the hurricane – like contaminated drinking water.

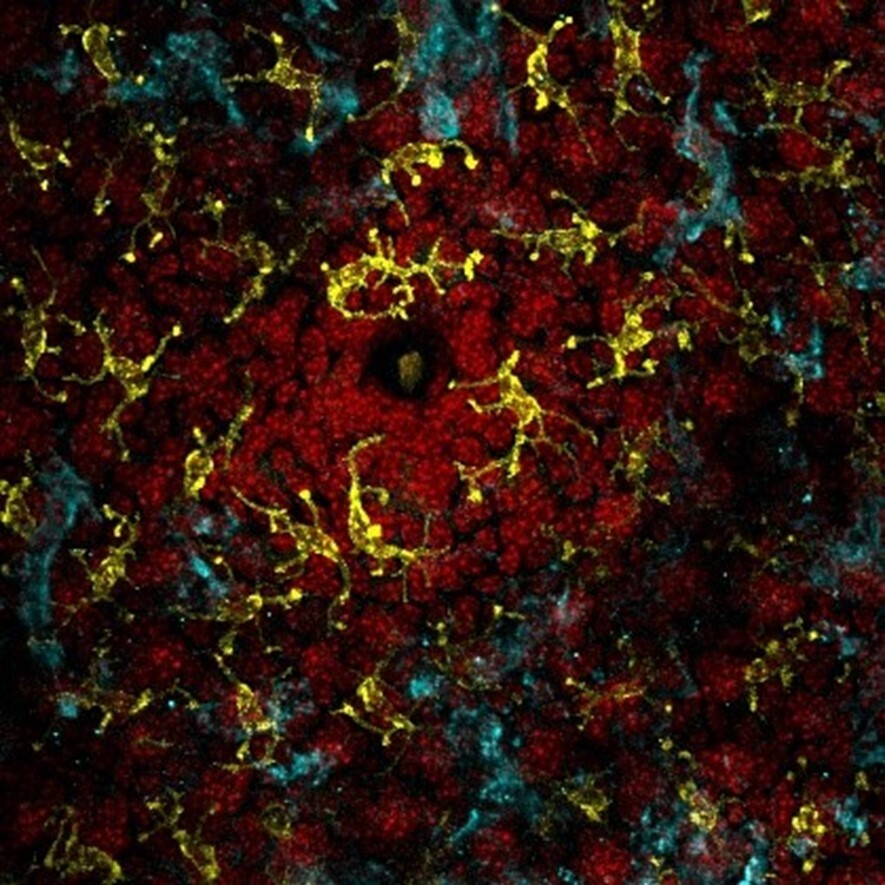

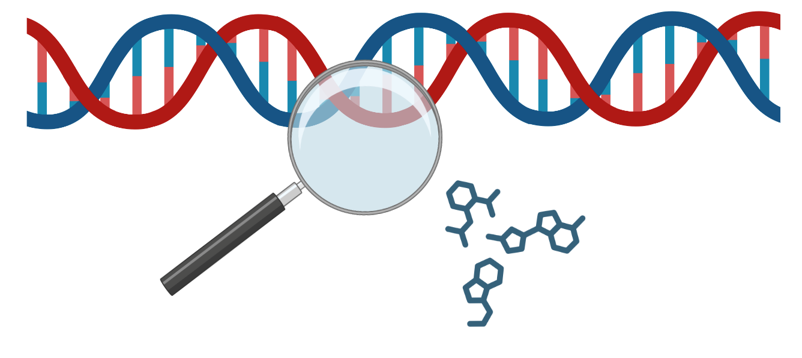

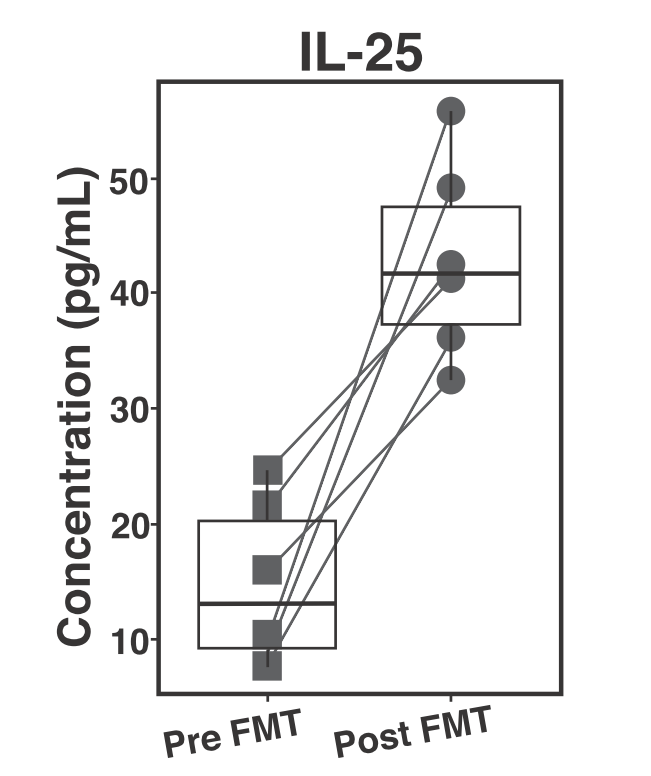

To better understand how the colonic environment changes in patients following FMT and if any clear pattern emerged that might suggest why people have persistent IBS symptoms, researchers collected biopsies and blood samples from patients before and after FMT treatment. They then performed molecular and biochemical experiments on those samples to investigate how the host immune system changes in response to FMT. For example, they measured the levels of several proteins that act as messengers carrying information between immune cells, called cytokines. One of these proteins, Interleukin 25 (IL-25), was significantly increased following FMT (Figure 3). This is of particular note because IL-25 is known to recruit anti-inflammatory cells and is generally involved in what is called type 2 inflammation3. When your body fights an infection there are two phases to the immune response. Phase 1 eliminates the imminent danger and is called type 1 inflammation and phase 2 cleans up and resolves the damages left behind from phase 1. This is referred to as type 2 inflammation.

In your colon this would be equivalent to the national guard coming into the city to eradicate the acute threat, C. diff,and then humanitarian aid workers ( IL-25) coming in to nurse the returning citizens back to health and organize a citizen-led cleanup effort: the type 2 inflammation. The finding that IL-25 levels are increased suggests that triggering a type 2 immune response following FMT might be important to restore the colonic environment to a healthy state. Although IL-25 levels were increased in all of the patients, regardless of continued IBS like symptoms, this suggests an avenue of further investigation as the sample size in this study was quite low. Based on their results, the scientists that conducted this study suggest that supplementing FMT with an intervention that would increase levels of IL-25 may allow physicians to develop a standardized, univeral, C-diff treatment and ultimately be able to conduct large clinical trials to determine if there are patterns that emerge among patients with persistent IBS symptoms following FMT.

You are now two years out from your procedure with no recurrent C-diff infections, you are very thankful you had a FMT and your gut microbiome is thriving. In fact, you have even recruited many of your friends to become fecal transplant donors with OpenBiome, a U.S. based non-profit stool bank that is working toward making safe, reliable, fecal samples accessible for FMT. In addition to OPenBiome, there are other stool banks popping up all around the world including the Microbiome Treatment Center at the University of Birmingham.

Link to the original post: Jan N, Hays RA, Oakland DN, Kumar P, Ramakrishnan G, Behm BW, Petri WA, Jr, Marie C. 2021. Fecal microbiota transplantation increases colonic IL-25 and dampens tissue inflammation in in Patients with Recurrent Clostridioides difficile

1. van Nood, E. et al. Duodenal Infusion of Donor Feces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 407–415 (2013).

2. Deng C, Peng N, Tang Y, Yu N, Wang C, Cai X, Zhang L, Hu D, Ciccia F and Lu L (2021) Roles of IL-25 in Type 2 Inflammation and Autoimmune Pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 12:691559. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.691559

Featured image: By author ; https://www.vectorstock.com/royalty-free-vector/viruses-cartoon-bacteria-emoticon-character-vector-21314254